When fun isn’t enough

This article is based on a talk I presented on the Tehran Game Convention. Slides are available here. Therefore, loss management instead of reward distribution becomes the main attribution of a game designer doing a bittersweet game. It’s a hard job, but a challenging and rewarding one, just like the desired player’s experience. If the game designer’s quest is successful, the resulting game shall be wrapped around contrasting feelings of joy, confusion, apprehension and much more, and therefore a much more faithful representation of real-life occurrences.

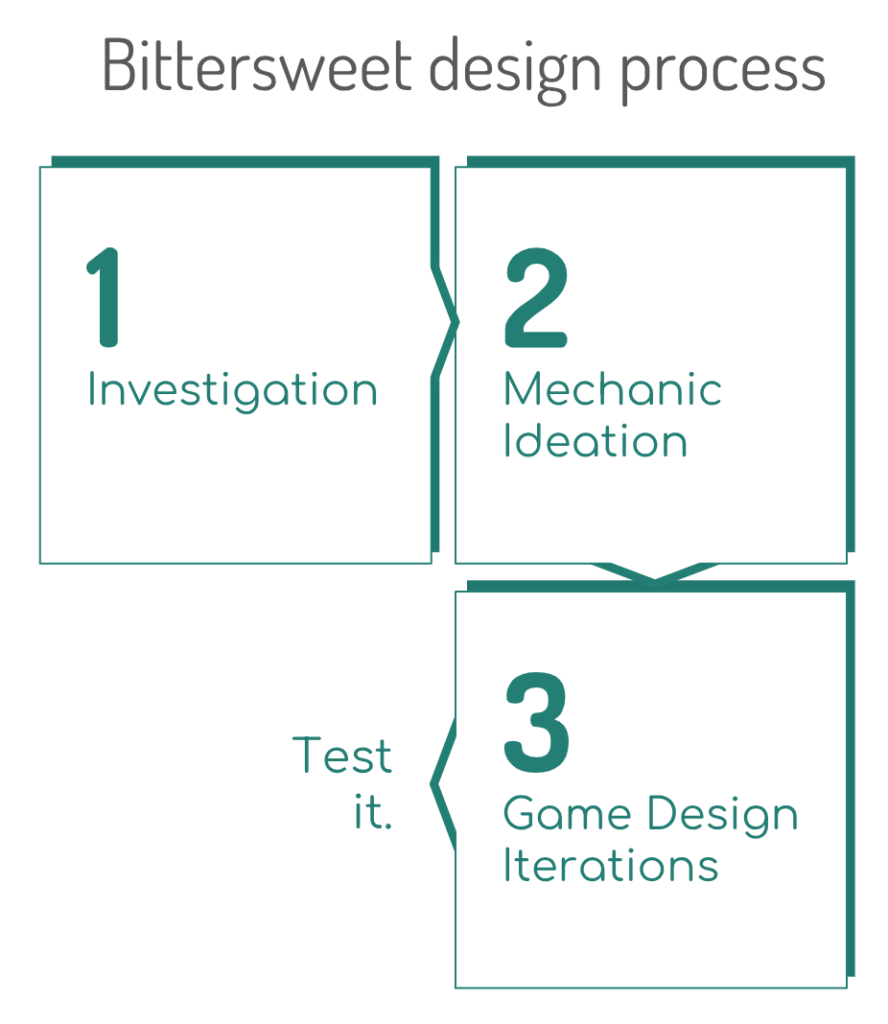

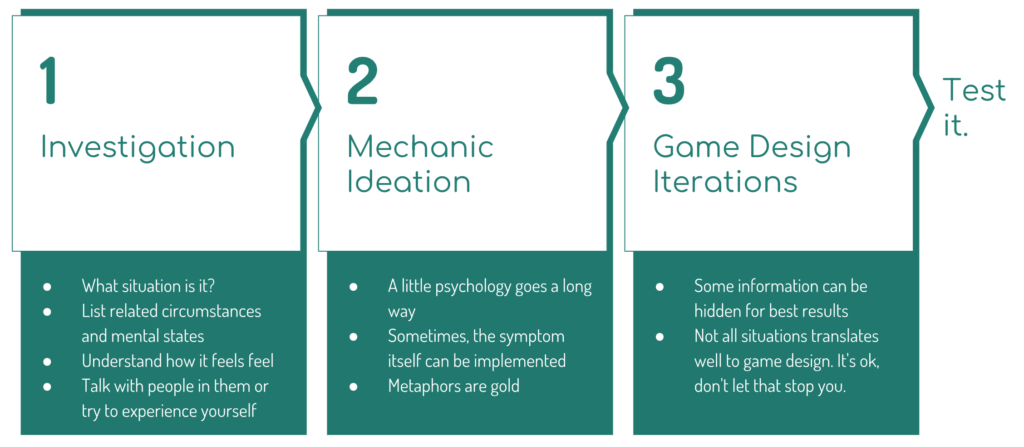

On my previous text, we discussed games in which the mechanics themselves are not focused only on positive reinforcement. Since this is not one beaten path in game design, there are not many examples to study or follow, which makes bittersweet game design particularly challenging. Now, we are going to explore how to achieve this, according to my own method. This is not the recipe for bittersweet game design but rather a recipe, the one I discovered doing Rainy Day. If you have your own, please share!

Form

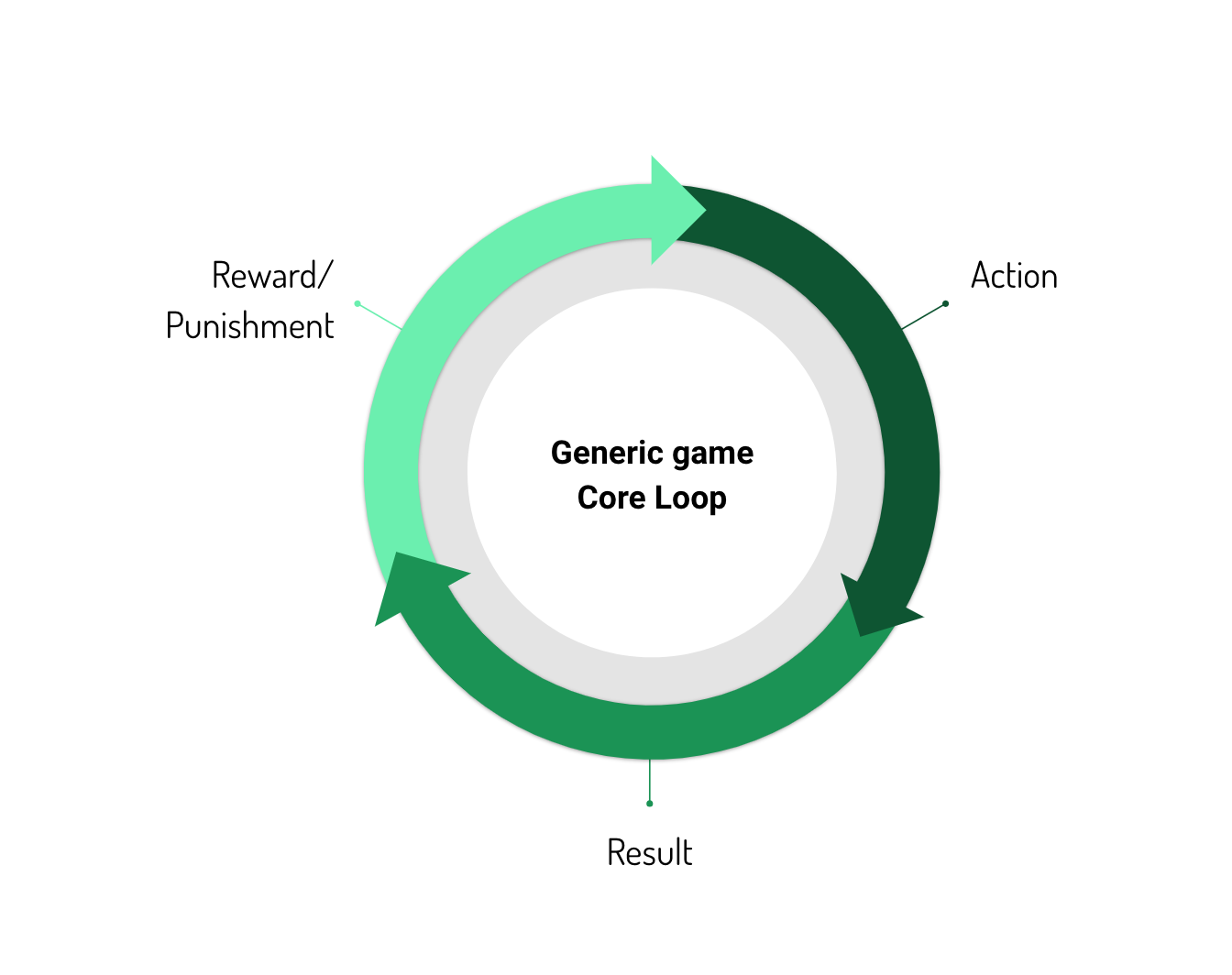

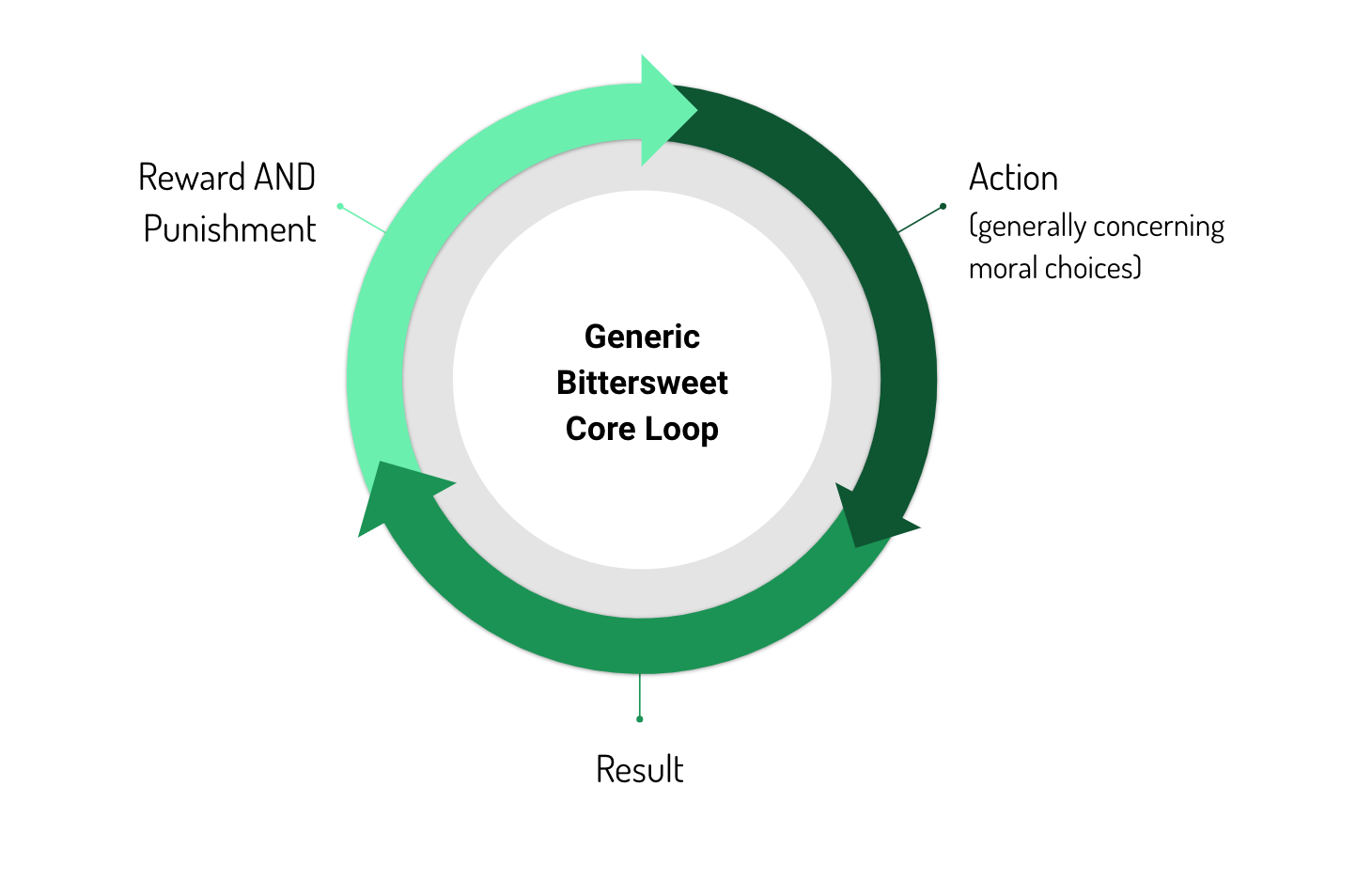

If we go back to the generic core loop we can see it does not explain a bittersweet design. The basic core loop uses rewards to endow the player for behavior they are supposed to repeat and uses punishment to squash what they are not supposed to be doing. In bittersweet games, however, positive reinforcement is used together with negative context or consequences in various levels of frequency in order to achieve a wider range of feelings while still keeping the player engaged.

So desirable behaviour or actions are not as crystal clear, by design.

Let’s remember Papers, Please. At the beginning of the game, you learn about the bureaucratic processes you need to be performing as the protagonist. The critical judgment of the papers you receive, trying to find if they are in order and not falsified, and the correct movement and usage of stamps are the gameplay. The complexity of both processes keeps increasing as you progress as rules change and more steps are added. That’s it, that’s all of it.

And yet, the core gameplay does not even start to describe your experience in Papers, Please because sorting, judging and stamping papers are only the ground level mechanics in which the bigger gameplay emerges. Every person whose papers you act on has a story. A story they tell you while you “do your job” of performing the gameplay. You can ignore the stories, at least in the beginning, but the consequences of this start to show up in the bigger picture of events, on how your country goes or even your existence as the protagonist. So, doing exactly what the core mechanics ask does not reward you and even punishes you.

You can try to go the opposite way, fuck mechanics, let’s go context. Let’s hear all stories and act as your moral compass would ask you to. However, this is not your way to succeed either, as this results on you and your family starving or worst.

The only way forward is something in between, so you cannot only be another clog in the system following the gameplay (and not being rewarded for it) neither can you take the high-horse moral path (and being punished by it). The only path is compromising, save some, lose some, and keep surviving. Just like, you know what, real life.

In theory, all games are made up of choices, even if unconscious, but what differs bittersweet games is that player’s choices will not always lead to positive reinforcement and even when they do there are losses. Loss management and adjustment, instead of reward hoarding is the name of the game for the player and no choice is ultimately better than the other. Players are actually eliminating worst outcomes. Not all good job gets rewarded, some good deeds get punishments. You have to feel your way along and live with the consequences.

The way Papers, Please weights down the reward in the core loop is by adding moral context to it, making the player feel dirty for doing what they were taught to by the game. The player cannot ignore the moral context of all their actions because this will end their run as well. However, Papers, Please also does not reward the player by doing what is morally right and, in fact, often punishes them by deductions to their payments on in more severe ways.

In other words, yes, it is very possible to convey complex feelings using the gameplay and its contexts, making every iteration of the game loop being a complex choice in itself. Though it is impossible to completely run away from positive reinforcement, it is possible to use it alongside some sort of punishment. For instance, a mechanic reward can be punished morally and the other way around. Conditioning, flawed rewards, and random outcomes also can be used in a way that influences the player to expect certain results, just to crush this expectation afterward.

Themes

The subjects of bittersweet games are not at all different from any other games: war, human relationships, survival, death, etc. What does differ is how these subjects are approached.

All games are simplifications or abstractions of things, so it isn’t surprising that complex themes such as armored conflicts are depicted in a rather unidimensional way. Generally, it is as simple as the bad guys vs the good guys. Many games nowadays do indulge for some shades of grey in the middle, however, it is still very clear who the hero, despite their faults, and the villain, despite their qualities, are.

Bittersweet games, as simplified they may be, don’t compromise as easily in moral values such as good or bad. Nothing in life is as simple as right or wrong, our decisions don’t exist in a moral vacuum in which our intent is the only possible outcome. Papers, Please illustrates this beautifully because all good deeds you make can become deductions to your paycheck which can lead to the death of your family, who is completely innocent of your actions. On the other hand, being a cog in the system and following all the rules may guarantee your family safety, but not of your countryfolk or even your own.

It is no surprise then that more often than not bittersweet games thrive especially in themes we as a society still have issues navigating morally. Border patrol, refugee crises, body autonomy, abusive relationships, mental illness, the list is endless.

Finally, a good bittersweet game is not only the story of only one individual because no one knows or have been through all the possible situations the theme of the game entails. To fully represent the intricacy of the theme, the game designer – even being themselves a survivor of the situation the game is about – should not count only on their personal experiences alone. Games are interactive and even though they lived through it and want to tell their perspective, they lived through one run of it. Their choices are theirs alone and could only be picked once. In order to create a fully fleshed experience in which the player can choose different paths that result in different outcomes, it is essential to talk with different people about their own experiences in this situation.

This is particularly true and unsurprisingly hard to remember when the game is a solo-dev work. I, for instance, got so caught up in developing Rainy Day sometimes that I added some choices to the player just to realize I, myself, never really took them in my life, not even once. Talking to other people with different levels of anxiety and depression gave me a very different perspective of how these illnesses can impact one’s life and it helped me to create a much richer experience in the game. Rainy Day loosely represents how I felt like; however, not every single option or action are things I did or would do myself. They are things people in that mind space could do, things I did or other people did and were weaved together in one single experience for the player to explore.

Process

So, how to create game mechanics that are challenging and engaging while not being too messy or dull? How to approach themes that are taboo or difficult to grasp in a respectful way?

There are no rules here, this is all uncharted territory. I have, however, adventured myself in them while working on Rainy Day, and so, developed my own process. I’m not claiming that this is the only or the best way to do it, it merely is my way of doing it.

And, most importantly, repeat!

Finally

As game designers aiming to add emotional complexity to our mechanics, maybe the best approach is to aim for a bittersweet design: difficult context intercalated with positive hooks. I strongly believe that interweaving negative emotions in the core loop itself in a way that is reasonably balanced is the biggest challenge a game designer can have. Not only it is hard to measure the sweet and bitter doses in a way that it feels hard but fair, but also this sort of loop has not yet been explored enough so we can know its limitations. Fun-driven loops are everywhere, we have references. Bittersweet ones, not that much.

However, the balance between reward and punishment is a constant in game design so how is this different from game design 101? Well, in most games loss and punishment is something to be avoided and contexted as an unwilling result. In games that willfully aim to evoke negative feelings, the loss is not a setback in the journey; it is an irrevocable part of it. The loss becomes a guest and functioning part of the design and game objectives. It must be absolutely impossible to play without losing something and, consequently, being invited to feel something.

Therefore, loss management instead of reward distribution becomes the main attribution of a game designer doing a bittersweet game. It’s a hard job, but a challenging and rewarding one, just like the desired player’s experience. If the game designer’s quest is successful, the resulting game shall be wrapped around contrasting feelings of joy, confusion, apprehension and much more, and therefore a much more faithful representation of real-life occurrences.