When fun isn’t enough

This article is based on a talk I presented on the Tehran Game Convention. Slides are available here. This post was also featured at Gamasutra.

“Videogames are supposed to be fun”

We pat ourselves in the back in understanding. Finally, some good old sense was spurred in this mad conversation. Tic tac toe comes to mind,

As we grew older, the games we played changed in character and risk, but one thing

We enter this activity with many doubts, bewildered by the tech, by our peers or even by our own creations. The doubts fade when we immerse ourselves in this playful bliss, drip by drip. We never question why we engage it in the first place, do we? That’s all too clear, questioning that would be equal to query the truthiness of our holy scriptures.

Fun.

That’s why we create games, right? To create that lovely, lovely endorphin rush.

In all seriousness, are they?

If you take into consideration most of what is considered as academic research on games and

All these researches can be summarized in behavioral psychology’ positive reinforcement. If the subject receives a positive stimulus while doing the action, both things become intertwined to a point when the action itself becomes the reward, even without the stimulus.

If, when you move your avatar to collide to with a yellow spherical object, we give you imaginary points and play a pleasant sounding effect, sooner or later the sound itself becomes positive. In the same way, if a not so pleasant sound plays every time something not so good happens, the sound itself becomes entangled with bad feelings.

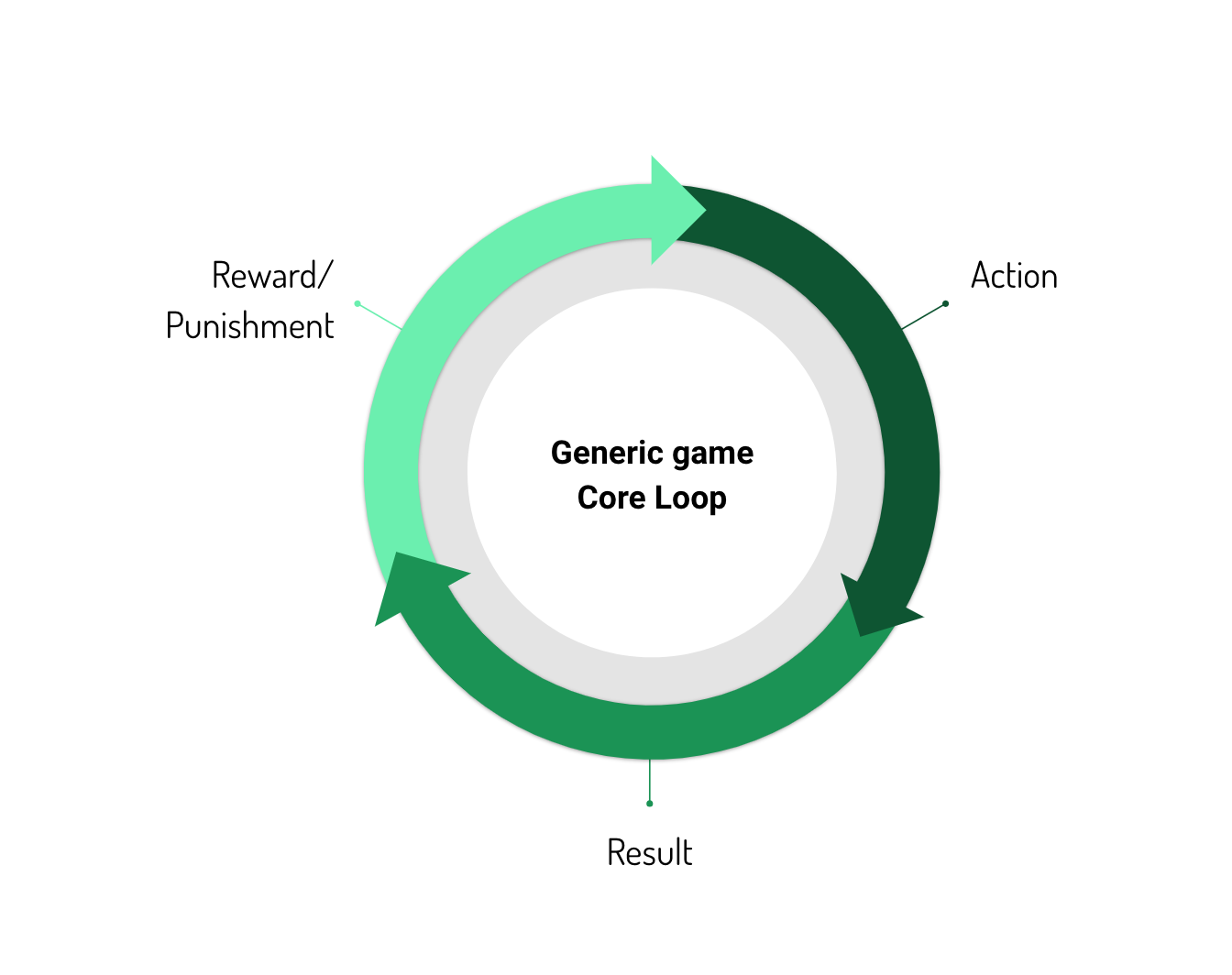

Reinforcement is the basis of the core loop concept that we use

Depending on the game, the actions change. For instance, in a match-three game, the action would be moving the pieces, the result would be forming a block or not, the reward depends on the game but generally involves the blog of similar pieces being destroyed. Most of these games don’t have harsh punishments for error, but they might have an indirect punishment such as

Behaviour science is very advanced in the of the use and results of reward-based reinforcement.

But science is not an impartial bystander of human knowledge. Science is question-driven and we tend the ask the questions on subjects we are more aware of. It is not by chance Huizinga study appeared in the 1930’s, when the Olympics was becoming a cultural (and political) phenomenon, making games and sports status on society skyrocket. It is also not by chance that we study more frequently pleasant and profitable (as

Since the commercial establishment of

Finding the feels (all of them)

But we are way past these days of introduction. Videogames are a thriving industry, on the reach of every human on this planet that has any access to the internet.

As a whole new medium, games can and should provoke all rage of human emotions and reactions and question the boundaries of its language in every opportunity. And yet,

But

Some games have already portrayed negative feelings in compelling ways, ways which I propose a new categorization.

Bitter Ending

That’s when a game presents negative feelings towards the end while relying on established positive reinforcing game mechanics. Generally, these negative feelings are a plot-twist, which means they are much more content related than gameplay related. Braid is an example of this structure, the player is lead to believe they are progressing toward saving the princess, realizing only in the end that the princess does not want to be saved (at least, not by the protagonist). You are the creep she wants to get away from, boo hoo.

There are many many other games that do that, but I don’t want to give you spoilers if you haven’t played them. If you don’t mind, here is a handy list of some of them.

Surprise Bitterness

That’s when designers want to highlight the tense or dangerous content of a particular moment in a game. The main mechanics and gameplay are crafted as pleasant and engaging as intended throughout the game. However, in a particular moment or space in the game, mechanics are subverted to force the player to feel the protagonist’s distress or the thickening of the plot.

For instance, on the torture scene in Metal Gear Solid when the player’s movements are restricted, conveying Snake’s precarious situation. This restriction is an opposition to the whole gameplay, before and after, and exists solely to convey Snake’s distress to the player. The player is no longer a bystander, they are part and victim of this break on the Geneva convention.

Surprise ou dramatic bitterness is a very effective way to draw player’s attention to this particular moment in the game while not being too risky since the main is intact through the game.

BitterSweet

Bittersweet is when the game can make the player feel negative feelings while they are engaged in the game itself. This is not an easy balancing to do, especially since we have so little studies around it and only a few games to use as examples.

Some games, however, do this seamlessly.

- Papers, Please – The player has to decide the fate of many applicants in every game-day. This involves mixed feelings because while the mechanic is compelling and interesting, the context of each applicant’s narrative and hopes weights in the player decision. Also, at the end of every game-day, the player is faced with the impact of their choices both in his family (“score” screen) and country (newspaper and warnings from their bosses) contexts. Complex gameplay emerges from a simple mechanic interweaved with very negative context and difficult moral choices.

- This War of Mine – The loss aversion mechanic in This War of Mine that constantly reminds the player of the scarcity and seriousness of the characters’ situation.

- Bury me, my love – Though it uses a very simple mechanic of emulating a chat between two people, the themes and the script take the player to the next step of

caring . You and your partner live in Syria (yes, civil war Syria) and you two together have been saving money to get away from the conflict. Since you what you put together is not that much and in economies razed by war things tend to cost more than they should, you two decide it is better to Nour, your partner, to go alone. Nour is making her journey, but she trusts your judgment and will always ask your opinion when she comes upon a crossroad. She will not always follow your judgment but she always check-in to know what you have been up to. The result is both gut-wrenching and heartwarming. - Dys4ia – Anna Anthropy took her everyday frustrations and the feeling of being an outsider and displayed in a series of discomforting and yet interesting mechanics. Though this game will not give the player the full experience of what it means to be a transgender woman in our society, it is a fair introduction.

- Rainy Day – I don’t feel like talking about this game again, please refer to this text.

Both design and content are used in these games to achieve the bittersweet result, however, the core loop is the basis of everything.

Approaching dubious and compounded themes (such as moral dilemmas or social situations) in a multifaceted way adds to the complexity of the loop, but without the bittersweet loop, you cannot achieve the ambiguity that is the heart and essence of a bittersweet game design.

Let’s talk about each these areas separately, in a future text.

Very useful for game designers like me. Liked it!!